Away from my desk for a while. So I’m offering up some previous posts you may not have seen. This one published last year is completely relevant, because thoughts of our life left behind in the Brooklyn house still pop up now and then. Enjoy!

Local historian Steve Banks gave another riveting talk a few weeks ago, this one about the history of traffic across this valley. Since then, I’ve been caught up in a sort of time travel.

Local historian Steve Banks gave another riveting talk a few weeks ago, this one about the history of traffic across this valley. Since then, I’ve been caught up in a sort of time travel.

I used to have the feeling that this Old West was much younger than the Back East I left behind. It must be part of the pioneer spirit you still feel out here, a sense of freshness and opportunity that reaches back from today’s new arrivals to the first intrepid white explorers.

Lately, I’ve been checking dates and making timelines. They parallel each other and resonate in very odd ways.

These four walls account for part of my confusion about time. They’re made of huge logs felled nearby and chinked warmly together, much as the original settlers made their cabins. Our new house looks historic, but it is only decades old — far younger than the Victorian brownstone we left behind, which was built in 1880.

The brownstone is 4 stories tall, has 4 bedrooms, and originally had a dining room and a receiving room for guests waiting to be admitted to the living room. It was remarkably modern for having central heating, fired by a coal furnace at the bottom.

The brownstone is 4 stories tall, has 4 bedrooms, and originally had a dining room and a receiving room for guests waiting to be admitted to the living room. It was remarkably modern for having central heating, fired by a coal furnace at the bottom.

In or around the same year it was built, Oran M. (“Old Man”) Clark, the first settler in this Wyoming valley, built his the first log cabin here — a windowless, one-room structure near the confluence of the Dunoir Creek and the Wind River. It too had “central heating,” People recalled that he often left the door open in winter so that he could run a huge log right across the middle of the room into the fireplace on the opposite wall. He would shift the log forward as it burned.

Clark didn’t file a homestead claim when he built the cabin, but he did claim to own the valley. Legend has it that in 1883, he raised his shotgun and ran off a party that included President Chester A. Arthur. He reportedly said that he had to give permission for anyone to enter the valley, and they didn’t have it. Wise men, they went to Yellowstone by another way.

For some reason he did, however, welcome John Burlingham and his son, who had come to Dubois to guide some dudes from Back East on a fishing trip. In fact, he coaxed the two men to return with their families, which they did in 1889.

For the first winter, the entire party stayed in Clark’s small, windowless log cabin. The following year they completed their own cabin, a few miles down the river. It was also windowless, with a dirt floor and a camp stove served by a pipe through the roof. A year later, Mahalia Burlingham gave birth to a stillborn daughter. Her husband John became the sought-after fiddler for dances across the entire region. He often left Mahalia alone with the children for months on end.

According to Steve Banks, the first white man to visit the valley was probably a Kentuckian named John Dougherty. A fur trapper and trader, he fled south in 1810 from what is now Montana to escape an attack by Blackfoot Indians, crossing Shoshone Pass close to Ramshorn Peak and continuing down the Dunoir Valley to the Wind River. (This picture shows that valley.) A bullet from the attack remained in his side for the rest of his life.

According to Steve Banks, the first white man to visit the valley was probably a Kentuckian named John Dougherty. A fur trapper and trader, he fled south in 1810 from what is now Montana to escape an attack by Blackfoot Indians, crossing Shoshone Pass close to Ramshorn Peak and continuing down the Dunoir Valley to the Wind River. (This picture shows that valley.) A bullet from the attack remained in his side for the rest of his life.

Steve says that location, at the confluence of the Dunoir Creek and the Wind River about 12 miles west of the current town of Dubois, was like the Times Square of the Old West. The Valley of the Dunoir had been the north-south artery toward the crossroads of a trade and migration route used by native Americans for time unknown. (The area has been part of the migration route for ancestors of the Shoshone for thousands of years.)

Early fur traders and explorers — men such as John Colter, John Hoback, and Jedediah Smith — passed this way, often guided by the natives.

In 1811, a year after John Dougherty came down the Dunoir Valley with a bullet in his side, Wilson Price Hunt came through with a party of 68 people and 200 horses. Hunt was a co-owner of John Jacob Astor’s American Fur Company, headed toward Fort Astoria on the Columbia River in the northwest, hoping to establish fur trade with Russia and China.

In 1811, a year after John Dougherty came down the Dunoir Valley with a bullet in his side, Wilson Price Hunt came through with a party of 68 people and 200 horses. Hunt was a co-owner of John Jacob Astor’s American Fur Company, headed toward Fort Astoria on the Columbia River in the northwest, hoping to establish fur trade with Russia and China.

Steve pointed out that Hunt’s party and their horses would have filled two Greyhound buses and 6 semi trucks. It was probably the largest single group of people ever to visit this valley. No settlement existed here at the time, except for a small Shoshone village.

The party had run out of food by the time they reached the base of the Dunoir. The natives, ill-prepared to feed them, advised Hunt to continue southward, crossing the Wind River, and over the mountains toward the Green River, where there were plenty of bison. The hunting detour cost them two weeks of progress; they should have headed west, upriver, where a friendly fort was only a few days away.

Frontiersman and explorer Jedediah Smith came this way about a decade later, in the winter of 1823-24. He brought with him a fur trapper named Daniel Potts, whose family owned Valley Forge in Pennsylvania. Potts was the first man to record a description of the geysers in what is now Yellowstone.

He also described our valley. “From thence across the 2d range of mountains to Wind River Valley …” he wrote in a letter on July 16, 1826. “Wind River is a beautiful transparent stream, with hard gravel bottom about 70 or 80 yards wide, rising in the main range of Rocky Mountains … The valleys near the head of this river and its tributary streams are tolerably timbered with cotton wood, willow, &c. The grass and herbage are good and plenty, of all the varieties common to this country. In this valley the snow rarely falls more than three to four inches deep and never remains more than three or four days, although it is surrounded by stupendous mountains.”

He also described our valley. “From thence across the 2d range of mountains to Wind River Valley …” he wrote in a letter on July 16, 1826. “Wind River is a beautiful transparent stream, with hard gravel bottom about 70 or 80 yards wide, rising in the main range of Rocky Mountains … The valleys near the head of this river and its tributary streams are tolerably timbered with cotton wood, willow, &c. The grass and herbage are good and plenty, of all the varieties common to this country. In this valley the snow rarely falls more than three to four inches deep and never remains more than three or four days, although it is surrounded by stupendous mountains.”

The West was younger, yes, but not by as much as I thought. As Dougherty was fleeing down the Dunoir and Hunt’s party was pleading for food with Shoshones in a mountain village a year later, my former home town of Brooklyn was just a small settlement across a wide river from Manhattan.

It didn’t incorporate as a village until 1817, only about seven years before Potts crossed this valley and saw the geysers. In 1898, Brooklyn was swallowed up in the creation of the great city of New York.

Twelve years after that, “Old Man” Clark froze to death, alone in his cabin, during a winter storm. His grave sits atop a small hill, marked by an obelisk and surrounded by a wrought iron fence.

Twelve years after that, “Old Man” Clark froze to death, alone in his cabin, during a winter storm. His grave sits atop a small hill, marked by an obelisk and surrounded by a wrought iron fence.

He had left money to buy ample whiskey for a wake. It took many tries for the mourners, who had stoked themselves well with his whiskey in front of his fireplace, to succeed in sliding his coffin up that slope over the icy ground.

But they did. Here is his grave.

© Lois Wingerson, 2018

You can see new entries of Living Dubois every week if you sign up at the top of the right column at www.livingdubois.com.

I ran into Gareth a few days ago at the Cowboy Café. Over breakfast he was working on a draft of a white paper.

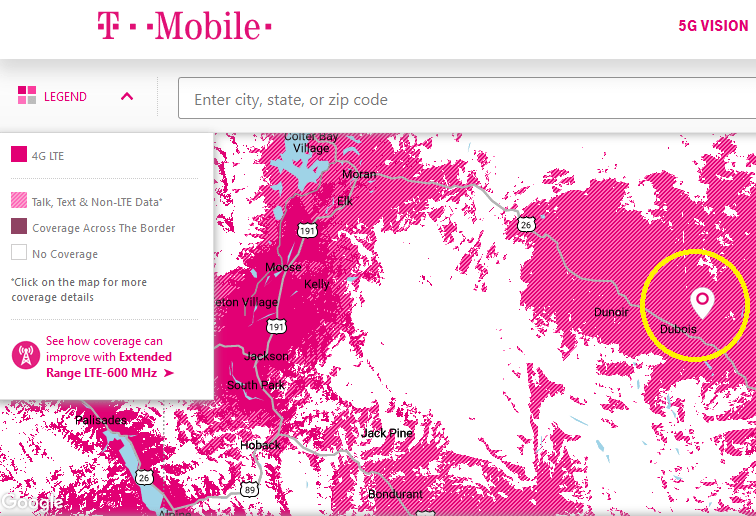

I ran into Gareth a few days ago at the Cowboy Café. Over breakfast he was working on a draft of a white paper. The first step in investigating Dubois, Gareth told me this week, was contacting DTE, our Internet provider. This wasn’t so crucial for Sharon, the former head of a private school in Steamboat Springs. But it’s essential for Gareth, who is an information architect with a firm that provides cybersecurity services for large corporations around the world. His work demands peerless high-speed Internet, and the fact that DTE provides fiberoptic service in town was a strong selling point for Dubois.

The first step in investigating Dubois, Gareth told me this week, was contacting DTE, our Internet provider. This wasn’t so crucial for Sharon, the former head of a private school in Steamboat Springs. But it’s essential for Gareth, who is an information architect with a firm that provides cybersecurity services for large corporations around the world. His work demands peerless high-speed Internet, and the fact that DTE provides fiberoptic service in town was a strong selling point for Dubois. It’s only a six hour drive north through Baggs and Rawlins to reach Dubois, but for Gareth and Sharon, the trip took far longer. Finding their next home, Gareth said, required “a lot of traveling in our RV.”

It’s only a six hour drive north through Baggs and Rawlins to reach Dubois, but for Gareth and Sharon, the trip took far longer. Finding their next home, Gareth said, required “a lot of traveling in our RV.” “Dubois has everything Jackson Hole has to offer,” Gareth told me. “You just hop into the car, and you’re in the Tetons. It’s all great.”

“Dubois has everything Jackson Hole has to offer,” Gareth told me. “You just hop into the car, and you’re in the Tetons. It’s all great.”

This has been our daytime view. We sit at the table by the window, gazing out toward the busy city street a few feet away, waiting. Beyond a certain point, all we could do was wait.

This has been our daytime view. We sit at the table by the window, gazing out toward the busy city street a few feet away, waiting. Beyond a certain point, all we could do was wait. At last, sometime last winter, our buyers materialized. We signed a contract. My husband arrived at the empty house the day before Easter, after a four-day drive eastward, and set about helping our son move out of the garden apartment, clearing out the basement and making other changes that had been agreed.

At last, sometime last winter, our buyers materialized. We signed a contract. My husband arrived at the empty house the day before Easter, after a four-day drive eastward, and set about helping our son move out of the garden apartment, clearing out the basement and making other changes that had been agreed. The expediter, meanwhile, seemed to have no urgency about completing the paperwork or coordinating the contractor and plumber. My husband came to New York three weeks before the scheduled closing (and three and a half months after hiring the architect) primarily to push the process forward.

The expediter, meanwhile, seemed to have no urgency about completing the paperwork or coordinating the contractor and plumber. My husband came to New York three weeks before the scheduled closing (and three and a half months after hiring the architect) primarily to push the process forward. I met former coworkers for drinks. I smiled at people on the street whose faces seemed familiar, and some greeted me. “I don’t see you in three years, and now I see you three times in a week,” said a woman whose name I recalled with effort. “What’s up?”

I met former coworkers for drinks. I smiled at people on the street whose faces seemed familiar, and some greeted me. “I don’t see you in three years, and now I see you three times in a week,” said a woman whose name I recalled with effort. “What’s up?” An assistant in the office may have been so embarrassed at this outburst that she took charge of the problem. She spoke to a public-advocate consultant in the buildings department, and got the job done at last, within a few days. We saw the final clearance on the website.

An assistant in the office may have been so embarrassed at this outburst that she took charge of the problem. She spoke to a public-advocate consultant in the buildings department, and got the job done at last, within a few days. We saw the final clearance on the website. Rounding a busy corner, during a visit to my old hometown of Brooklyn, I found a small group of people crowding the doorway to an office building and taking pictures on their phones.

Rounding a busy corner, during a visit to my old hometown of Brooklyn, I found a small group of people crowding the doorway to an office building and taking pictures on their phones. Hugging a corner beside the doorway, it glared back at us.

Hugging a corner beside the doorway, it glared back at us. Nonetheless the officer ran the crime–scene tape across the forward side of the barricade, further isolating the perpetrator from the crowd.

Nonetheless the officer ran the crime–scene tape across the forward side of the barricade, further isolating the perpetrator from the crowd. “Oh, sure. It’s a great life for them,” replied the female variety of that prominent species, the New York Knowitall. “But I wonder why this young one got stuck here.”

“Oh, sure. It’s a great life for them,” replied the female variety of that prominent species, the New York Knowitall. “But I wonder why this young one got stuck here.” I found myself musing about the odds that somehow this hawk would be transported to Dubois, just as I was not that long ago. Or as Game & Fish sometimes relocates a wayward bear up-mountain.

I found myself musing about the odds that somehow this hawk would be transported to Dubois, just as I was not that long ago. Or as Game & Fish sometimes relocates a wayward bear up-mountain. “Whenever you’re ready,” said the cashier at a sidewalk cafe, abruptly turning away when I took time to count out the exact change. There was no one else to serve; he was just irritated that I was not hurrying.

“Whenever you’re ready,” said the cashier at a sidewalk cafe, abruptly turning away when I took time to count out the exact change. There was no one else to serve; he was just irritated that I was not hurrying.

I returned from a visit to Texas on one of the last days in April. Boarding after a layover in Denver, I saw opaque ice crusting the window beside my seat. We taxied, got de-iced with orange spray, returned to the gate, de-planed, and waited for the weather in Jackson to improve.

I returned from a visit to Texas on one of the last days in April. Boarding after a layover in Denver, I saw opaque ice crusting the window beside my seat. We taxied, got de-iced with orange spray, returned to the gate, de-planed, and waited for the weather in Jackson to improve. My husband is away on business, and I seem to spend more time than usual looking out the window. The day after my return, I was startled to see four unusual creatures almost the size of horses, grazing as they ambled slowly across the meadow to the east.

My husband is away on business, and I seem to spend more time than usual looking out the window. The day after my return, I was startled to see four unusual creatures almost the size of horses, grazing as they ambled slowly across the meadow to the east. A friend suggested that these females may have been separated from their herd in the snowstorm. I hope they found their way back.

A friend suggested that these females may have been separated from their herd in the snowstorm. I hope they found their way back. The next day this lovely hawk chose to perch for a while on the balcony railing, just outside the netting that we use to keep the swallows from building mud nests under the gable. I’ve never seen a hawk so close, even in a zoo. Unfortunately the picture doesn’t show the lovely red feathered cap on the top of his head.

The next day this lovely hawk chose to perch for a while on the balcony railing, just outside the netting that we use to keep the swallows from building mud nests under the gable. I’ve never seen a hawk so close, even in a zoo. Unfortunately the picture doesn’t show the lovely red feathered cap on the top of his head. These are sights the tourists would covet — working cowboys, eagles, elk — but the tourists haven’t arrived yet. One joy of being here all year is that I can encounter these sights by serendipity — especially in this season, when so few visitors dare to come because the weather is chancy.

These are sights the tourists would covet — working cowboys, eagles, elk — but the tourists haven’t arrived yet. One joy of being here all year is that I can encounter these sights by serendipity — especially in this season, when so few visitors dare to come because the weather is chancy. A few steps later, I saw where it had come down the same slope I had just descended, but a bit farther to the west.

A few steps later, I saw where it had come down the same slope I had just descended, but a bit farther to the west. They call it Sheep Ridge, the one you can see from the main street in Dubois, but no bighorn sheep have grazed there for a long time. The herd is still around, but its population is plummeting. Why?

They call it Sheep Ridge, the one you can see from the main street in Dubois, but no bighorn sheep have grazed there for a long time. The herd is still around, but its population is plummeting. Why? The greatest concern is that these bighorns are extraordinarily prey to respiratory infections common among sheep. They harbor a half-dozen strains of the relevant bacteria, while wild sheep elsewhere in the West seem to be hosts to only two or three. Enough lambs are born to this herd each year, but only a handful reach maturity. Many of the ewes live on, chronically ill, to infect again and again.

The greatest concern is that these bighorns are extraordinarily prey to respiratory infections common among sheep. They harbor a half-dozen strains of the relevant bacteria, while wild sheep elsewhere in the West seem to be hosts to only two or three. Enough lambs are born to this herd each year, but only a handful reach maturity. Many of the ewes live on, chronically ill, to infect again and again. The Wyoming Game and Fish Department has won grants from four organizations to support the summits, and commitments of time and expertise from bighorn sheep specialists all over the West. One of the grants brought a panel of eight specialists on the bighorns to Dubois last month, where they shared their knowledge, listened to ours, and brainstormed.

The Wyoming Game and Fish Department has won grants from four organizations to support the summits, and commitments of time and expertise from bighorn sheep specialists all over the West. One of the grants brought a panel of eight specialists on the bighorns to Dubois last month, where they shared their knowledge, listened to ours, and brainstormed.

No solution will emerge quickly. We’ll remain in the dark about the root cause of the die-off for at least three years, while Montieth’s team completes its research.

No solution will emerge quickly. We’ll remain in the dark about the root cause of the die-off for at least three years, while Montieth’s team completes its research.